Understanding Rat Lifespan

Factors Influencing Rat Lifespan

Genetic Predisposition

Genetic predisposition significantly influences the correlation between rat developmental stages and equivalent human ages. Variations in DNA sequences determine metabolic rate, disease susceptibility, and longevity, which in turn affect the scaling factors used in age‑conversion tables.

Key genetic determinants include:

- Growth hormone receptor (GHR) variants – modify growth velocity and adult size, shifting the age at which rats reach developmental milestones.

- Insulin‑like growth factor 1 (IGF‑1) alleles – alter tissue repair capacity and lifespan, impacting the rate at which physiological aging progresses.

- Mitochondrial DNA haplotypes – affect oxidative stress resistance, influencing the onset of age‑related pathologies.

- Apolipoprotein E (APOE) isoforms – correlate with neurodegeneration risk, adjusting the equivalence of cognitive aging stages.

When constructing a rat‑to‑human age comparison chart, researchers incorporate these genetic factors to refine conversion ratios. For example, a rat strain carrying a longevity‑associated GHR mutation may be assigned a slower aging curve, resulting in a higher human‑age equivalent for a given chronological week. Conversely, strains with high‑risk APOE alleles receive accelerated scaling to reflect earlier onset of neurodegenerative markers.

Integrating genetic predisposition data ensures that age conversion tables reflect biological reality rather than relying solely on chronological benchmarks. This approach improves the relevance of rat models for translational research, allowing more accurate prediction of human outcomes based on rodent experiments.

Environmental Conditions

Environmental variables shape rat growth rates, metabolic activity, and longevity, thereby influencing the numerical correspondence between rodent age and human age. Researchers must account for these factors when constructing or applying a rat‑to‑human age conversion chart.

Key conditions that alter the age equivalence include:

- Ambient temperature: Cooler environments slow metabolic processes, extending developmental milestones; warmer settings accelerate maturation, reducing the human‑year equivalent for a given chronological age.

- Relative humidity: High humidity increases respiratory stress, potentially shortening lifespan and shifting age ratios downward.

- Nutritional quality: Diets rich in protein and essential micronutrients promote faster growth, raising the human‑year conversion factor; nutrient‑deficient regimens delay development, lowering the factor.

- Housing density: Overcrowding elevates stress hormones, leading to earlier onset of age‑related pathologies and a higher human‑year equivalence for younger rats.

- Light cycle: Extended photoperiods stimulate hormonal cycles that can hasten development; reduced light exposure slows growth, affecting age mapping.

When interpreting a rat‑to‑human age table, adjust the baseline conversion (commonly 1 rat month ≈ 2.5 human years) according to the specific environmental profile of the study population. Failure to incorporate these adjustments yields inaccurate age comparisons and may compromise translational relevance.

Diet and Nutrition

Rats mature rapidly; a one‑month‑old rat corresponds roughly to a human toddler, while a two‑year‑old rat aligns with a middle‑aged adult. Nutrition must adapt to these accelerated life stages. Early growth demands high protein (18‑20 % of diet), readily digestible carbohydrates, and essential fatty acids to support skeletal and neural development. Calcium and phosphorus ratios of 1.2 : 1 prevent premature bone loss during the rapid growth phase.

Adult rats (equivalent to 30‑50 human years) require balanced energy intake to maintain lean mass without excess fat accumulation. A diet containing 14‑16 % protein, 4‑5 % fat, and fiber levels of 5‑7 % supports metabolic stability. Micronutrients such as vitamin E, selenium, and zinc become critical for immune competence and oxidative stress mitigation, mirroring human mid‑life health concerns.

Senior rats (comparable to humans over 60) experience decreased appetite and altered digestive efficiency. Formulations with reduced calorie density (12‑14 % protein, 3‑4 % fat) and increased digestible fiber aid gastrointestinal health. Supplementation with omega‑3 fatty acids, B‑complex vitamins, and joint‑supporting glucosamine addresses age‑related inflammation and mobility decline.

Key dietary adjustments by life stage:

- Juvenile (0–2 months) – high‑quality protein, calcium‑phosphorus balance, vitamin D.

- Young adult (2 months–1 year) – moderate protein, balanced fat, adequate fiber, antioxidant vitamins.

- Mature adult (1–2 years) – controlled calories, essential minerals, omega‑3 enrichment.

- Senior (2 years+) – lower calories, enhanced digestibility, joint‑support nutrients, probiotic inclusion.

Implementing these guidelines ensures that the rat‑to‑human age conversion framework reflects not only chronological equivalence but also appropriate nutritional support for each physiological stage.

Healthcare and Veterinary Care

Understanding how a rat’s chronological age translates to human years provides a practical framework for veterinary decision‑making. By aligning a rat’s life stage with comparable human milestones, clinicians can anticipate physiological changes, schedule preventive procedures, and tailor therapeutic protocols to the animal’s specific needs.

Veterinary assessments rely on age categories derived from the conversion chart. Juvenile rats (approximately 0.5–1.5 human years) require intensive growth monitoring, dietary adjustments, and early vaccination. Adult rats (3–7 human years) benefit from routine health examinations, dental checks, and screening for metabolic disorders. Senior rats (10+ human years) demand comprehensive geriatric care, including cardiac evaluation, renal function testing, and pain management strategies.

Typical interventions aligned with age groups:

- Juvenile (0.5–1.5 human years)

- Weekly weight tracking

- Nutrient‑rich diet formulation

- Initial immunization series

- Adult (3–7 human years)

- Biannual physical examinations

- Dental cleaning every 12 months

- Blood panels for glucose and lipid profiles

- Senior (10+ human years)

- Quarterly cardiovascular ultrasonography

- Renal function assays

- Analgesic regimen for arthritis or musculoskeletal degeneration

Applying the rat‑to‑human age equivalence enables owners and veterinarians to synchronize care plans with the animal’s physiological timeline, reducing the risk of age‑related disease and extending the quality of life.

The Rat-to-Human Age Conversion Concept

Why Compare Rat and Human Ages?

Comparing the lifespan of rats with that of humans provides a practical framework for interpreting experimental results, estimating developmental stages, and communicating findings to non‑specialists. By expressing a rat’s age in equivalent human years, researchers can align biological processes such as growth, puberty, and senescence across species, which simplifies the design and analysis of studies that use rodents as models for human health.

- Age conversion enables accurate extrapolation of drug efficacy and toxicity data from laboratory rats to anticipated human outcomes.

- It facilitates selection of appropriate animal ages for modeling specific human life phases, from infancy to old age, thereby improving relevance of disease models.

- Veterinarians and pet owners can assess health risks, nutritional needs, and preventive care schedules by referencing a rat‑to‑human age equivalence chart.

- Educators can illustrate comparative biology concepts, reinforcing understanding of metabolic rates, lifespan scaling, and evolutionary adaptations.

The utility of a rat‑human age comparison table extends beyond academic interest; it is a functional tool that bridges the gap between laboratory research and real‑world applications, ensuring that conclusions drawn from rodent studies are grounded in a relatable human perspective.

Limitations of Direct Conversion

Directly translating a rat’s chronological age into human years oversimplifies a complex biological relationship. The conversion assumes a uniform scaling factor, yet growth, maturation, and aging follow distinct patterns in each species.

Key limitations of a straightforward conversion include:

- Non‑linear development – Rats reach sexual maturity within weeks, while humans require years; a single multiplier cannot capture this disparity.

- Physiological divergence – Metabolic rate, lifespan, and disease susceptibility differ markedly, influencing how age impacts organ function.

- Environmental influence – Laboratory conditions, diet, and stress levels alter rat longevity, making a fixed conversion unreliable for varied settings.

- Strain variability – Genetic differences among rat strains produce divergent aging trajectories, which a generic factor ignores.

- Sex‑specific effects – Male and female rats exhibit distinct aging patterns, whereas a universal conversion treats both sexes identically.

Because of these factors, any table that pairs rat ages with human equivalents must be interpreted as an approximate guide rather than a precise equivalence.

Scientific Basis for Age Equivalence

Rats and humans differ markedly in physiology, yet systematic methods allow conversion of a rat’s chronological age into an approximate human equivalent. The conversion relies on measurable biological parameters rather than anecdotal scaling.

- Metabolic scaling – Basal metabolic rate (BMR) follows an allometric relationship (BMR ∝ mass^0.75). Because rats have a higher mass‑specific BMR, each rat day corresponds to several human days, especially during early development.

- Developmental milestones – Organogenesis, weaning, sexual maturity, and senescence occur at consistent relative ages across mammals. For example, rats reach sexual maturity at ~6 weeks, which aligns with human adolescence (≈13 years).

- Lifespan proportion – The average laboratory rat lives 2–3 years; humans average ~80 years. Dividing total lifespan yields a factor of roughly 30–40 rat years per human year, adjusted for non‑linear aging rates.

- Gene expression patterns – Comparative transcriptomics show synchronized activation of aging‑related pathways (e.g., mTOR, insulin/IGF‑1) at analogous chronological points, supporting the numerical scaling.

- Physiological markers – Heart rate, body temperature, and renal function decline follow comparable trajectories when expressed as a fraction of maximum lifespan, providing additional calibration points for the table.

These data sources are integrated into empirically derived equations (often logarithmic or power‑law forms) that generate the rows of a rat‑to‑human age comparison table. The resulting framework enables researchers to translate experimental findings in rats to human age contexts with quantified confidence.

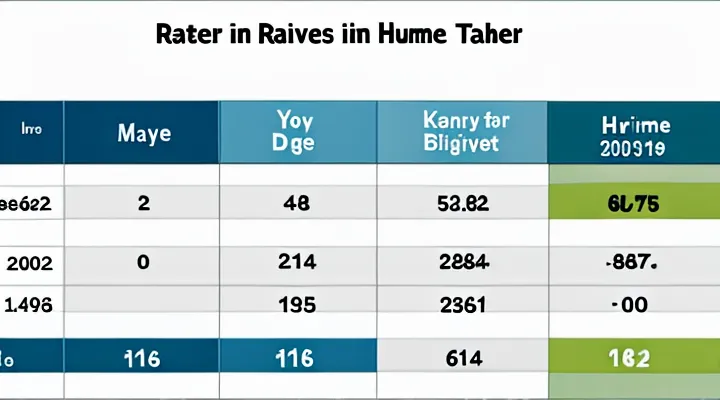

The Rat Age in Human Years Comparison Table

Interpreting the Age Chart

The conversion chart aligns a rat’s chronological age with its equivalent human age, allowing direct comparison across life stages. Each row represents a specific rat age in months or years, paired with the corresponding human age estimate. The chart’s scale is non‑linear: early months translate to large human age increments, while later years increase more gradually.

Interpretation requires attention to three core aspects:

- Developmental milestones – early entries (first 2–3 months) correspond to infancy and early childhood in humans; rapid growth phases are reflected by steep jumps in the human‑age column.

- Mid‑life alignment – ages between 6 and 12 months typically map to teenage years, indicating the rat’s transition to sexual maturity and increased activity.

- Senior period – ages beyond 24 months align with middle‑aged to elderly humans, showing a slower rise in the human‑age figure, which matches the deceleration of physiological decline in rats.

When using the chart, match the rat’s exact age to the nearest listed value; if the rat falls between two entries, interpolate proportionally. Apply the derived human age to assess health expectations, nutritional needs, and preventive care appropriate for the equivalent human life stage. This method provides a practical framework for veterinarians, researchers, and owners to gauge a rat’s developmental status against human benchmarks.

Common Rat Breeds and Their Lifespans

Fancy Rats

Fancy rats, a domesticated variety of Rattus norvegicus, typically live 2 to 3 years under optimal care. Their rapid early development means that a few months correspond to several human years, making age conversion essential for health monitoring and veterinary planning.

The age‑equivalence chart translates rat months into human years by applying a scaling factor derived from growth curves and metabolic rates. The table aligns key developmental milestones with comparable human ages, allowing owners to anticipate nutritional needs, reproductive timing, and age‑related health risks.

- 1 month ≈ 3 human years (early juvenile stage)

- 3 months ≈ 7 human years (adolescence, sexual maturity)

- 6 months ≈ 12 human years (young adult)

- 12 months ≈ 25 human years (full adult)

- 18 months ≈ 35 human years (mid‑life)

- 24 months ≈ 45 human years (senior)

Applying these equivalences helps owners adjust diet, enrichment, and medical check‑ups to match the physiological stage of their fancy rat, ensuring longevity and wellbeing.

Lab Rats

Lab rats serve as standard model organisms in biomedical research, with a typical lifespan of 2 – 3 years under controlled conditions. Their developmental milestones align with specific stages of human growth, allowing researchers to translate findings across species.

Age conversion relies on physiological markers such as sexual maturity, skeletal development, and metabolic rate. Early adulthood in rats (approximately 6 months) corresponds to early adulthood in humans, while senescence begins around 24 months, matching late‑stage human aging.

- 1 month ≈ 2 human years

- 3 months ≈ 8 human years

- 6 months ≈ 20 human years

- 12 months ≈ 35 human years

- 18 months ≈ 48 human years

- 24 months ≈ 60 human years

These equivalencies provide a practical reference for interpreting experimental timelines and extrapolating rat data to human health contexts.

Wild Rats

Wild rats typically live 1–2 years in natural habitats, considerably shorter than the average lifespan of domestic rats. Their rapid growth and early maturity mean that each month of a wild rat’s life corresponds to several human years.

- 1 month ≈ 3 human years

- 3 months ≈ 10 human years

- 6 months ≈ 20 human years

- 12 months ≈ 40 human years

- 18 months ≈ 55 human years

- 24 months ≈ 70 human years

These equivalences are derived from comparative metabolic rates and developmental milestones. Wild rats reach sexual maturity at about 6–8 weeks, a stage that aligns with human adolescence. Their accelerated aging reflects higher basal metabolic demands and exposure to predators, disease, and fluctuating food supplies.

Environmental pressures shorten the upper age limit for wild rats. Factors such as seasonal temperature changes, competition for shelter, and pathogen load can reduce the expected maximum human‑equivalent age from roughly 70 years to 50 years or less in harsh conditions. Consequently, the conversion chart provides a baseline; actual human‑equivalent age may vary with habitat quality and population density.

Key Developmental Milestones in Rats and Humans

Infancy and Childhood

Rats mature rapidly; the earliest stages correspond to distinct human developmental milestones. Translating these periods into a comparative age table enables researchers to align experimental findings with pediatric stages.

Infancy encompasses the first three weeks of a rat’s life. During this interval, neural circuits form, sensory systems activate, and weaning has not yet occurred. In human terms, the equivalent spans birth to approximately three months, representing the neonatal to early infant phase.

Childhood extends from the third to the sixth week after birth. At this point, rats achieve full locomotor independence, begin solid food consumption, and exhibit social play behaviors. The human counterpart ranges from three to twelve months, covering the latter infant period through early toddler development.

Key equivalences:

- 0–1 week (rat) → 0–1 month (human)

- 1–3 weeks (rat) → 1–3 months (human)

- 3–6 weeks (rat) → 3–12 months (human)

These mappings provide a clear framework for interpreting rat data within the context of early human growth stages.

Adolescence

Adolescence marks the transition from juvenile growth to sexual maturity in rodents, a phase that aligns with early teenage years in humans. In age‑conversion tables, the adolescent window for rats typically spans from 5 to 8 weeks of life, corresponding to roughly 12 to 16 human years.

- 5 weeks (rat) ≈ 10–12 human years – onset of rapid body growth, emergence of secondary sexual characteristics.

- 6 weeks (rat) ≈ 13–14 human years – peak of skeletal development, increased activity levels.

- 7 weeks (rat) ≈ 15–16 human years – consolidation of reproductive organ maturation, behavioral shifts toward independence.

- 8 weeks (rat) ≈ 17–18 human years – completion of physical maturation, readiness for breeding.

Physiological markers during this interval include a surge in growth‑hormone secretion, acceleration of bone lengthening, and the appearance of adult fur coloration. Behavioral observations reveal heightened exploratory activity, social hierarchy formation, and the establishment of mating behaviors. These attributes provide a reliable framework for aligning rat developmental stages with human adolescent milestones in comparative age charts.

Adulthood and Seniority

The conversion of a rat’s lifespan to human-equivalent years provides a practical framework for assessing developmental stages. By applying a standardized rat‑to‑human age chart, researchers and pet owners can align physiological and behavioral milestones with familiar human age categories.

Adulthood in rats begins after the rapid growth phase of the first two months. At this point, a rat’s age of 3 months corresponds to roughly 18 human years. The adult period extends to about 12 months, which translates to 30–35 human years. During this interval, rats exhibit stable reproductive capacity, mature immune function, and consistent activity levels comparable to those of a human in early to mid‑adulthood.

Seniority starts when a rat reaches one year of age. At 12 months, the rat’s age aligns with approximately 35 human years, marking the onset of senior status. By 18 months, the rat equates to about 50 human years, and at 24 months, the conversion reaches roughly 65 human years. Senior rats display reduced metabolic rate, increased susceptibility to chronic conditions, and altered social behavior, mirroring the health profile of elderly humans.

Typical rat‑to‑human age equivalents:

- 3 months → 18 human years (early adulthood)

- 6 months → 24 human years (mid‑adulthood)

- 12 months → 30–35 human years (late adulthood)

- 18 months → 50 human years (early seniority)

- 24 months → 65 human years (advanced seniority)

Understanding these equivalences enables precise health monitoring, dietary adjustments, and welfare planning that reflect the rat’s stage within the adult‑senior spectrum.

Practical Applications of Rat Age Conversion

Pet Rat Care and Health Monitoring

Nutritional Needs by Age

Rats progress through life stages much faster than humans, so their dietary requirements shift rapidly. When a rat’s age is expressed in human‑equivalent years, the transition from juvenile to adult and then to senior phases becomes apparent, allowing caretakers to align nutrition with physiological demands.

Juvenile rats (approximately 0–6 months, comparable to human children up to 10 years) need high‑quality protein to support rapid tissue growth, elevated calcium for bone development, and sufficient energy density. Recommended levels: protein 20–24 % of diet, calcium 1.0 % (dry matter), and metabolizable energy 300–350 kcal kg⁻¹ day⁻¹.

Adult rats (6–24 months, equivalent to human ages 20–50) require balanced macronutrients for maintenance and reproduction. Ideal composition: protein 16–20 %, fat 4–6 %, calcium 0.8 %, and energy 260–300 kcal kg⁻¹ day⁻¹. Micronutrients such as vitamin E and selenium should be supplied at levels preventing oxidative stress.

Senior rats (over 24 months, matching human ages 60+) experience diminished metabolic rate and reduced renal function. Diets should lower caloric content to 220–250 kcal kg⁻¹ day⁻¹, increase digestible fiber to aid gastrointestinal health, and maintain protein at 14–16 % to preserve lean mass. Phosphorus and potassium must be moderated to ease kidney load, while antioxidants (vitamin C, beta‑carotene) support immune competence.

Key adjustments across life stages:

- Increase protein and calcium during growth; taper both as rats age.

- Reduce overall energy density for seniors to prevent obesity.

- Elevate fiber and antioxidant intake in later life to mitigate age‑related decline.

- Monitor water consumption continuously; dehydration risk rises with age.

Age-Related Health Issues

Rats experience health problems that parallel human aging, and a conversion chart clarifies when these issues emerge. Understanding the correspondence helps researchers select appropriate animal models for studying age‑related diseases.

-

Early adulthood (≈ 6 months rat ≈ 20‑30 human years)

• Muscular strength peaks, but subtle metabolic shifts begin.

• Occasional respiratory infections appear, reflecting early immune system challenges. -

Middle age (≈ 12‑18 months rat ≈ 40‑55 human years)

• Decline in renal function manifests as reduced glomerular filtration rate.

• Cardiac hypertrophy increases, with elevated blood pressure and early atherosclerotic lesions.

• Cognitive performance shows measurable slowdown in maze navigation and object recognition. -

Senior stage (≈ 24‑30 months rat ≈ 65‑80 human years)

• Osteoarthritis develops, producing joint stiffness and reduced mobility.

• Vision loss progresses due to cataract formation and retinal degeneration.

• Neurodegeneration emerges, evidenced by decreased dopamine levels and motor coordination deficits.

• Immune senescence leads to heightened susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections. -

Advanced age (≥ 36 months rat ≈ 90+ human years)

• Severe sarcopenia reduces muscle mass dramatically.

• Chronic kidney disease advances to end‑stage renal failure.

• Multiple organ dysfunction becomes common, often culminating in reduced lifespan.

The conversion chart aligns each rat age bracket with the corresponding human age range, allowing precise timing of interventions such as dietary modifications, pharmacological trials, or genetic studies aimed at mitigating these health issues. Selecting rats at the appropriate life stage ensures experimental relevance and improves translational value.

Research Implications

Animal Models in Gerontology

Animal models provide measurable, reproducible data for studying aging processes, and rodents dominate gerontological research because of short lifespans, well‑characterized genetics, and physiological parallels to humans.

Rats live approximately 2.5–3 years under laboratory conditions. Translating rat age to human age relies on empirical scaling based on developmental milestones, metabolic rates, and mortality curves. A typical conversion chart lists the following equivalences:

- 1 month ≈ 3 human years (infancy)

- 3 months ≈ 15 human years (early childhood)

- 6 months ≈ 30 human years (adolescence)

- 12 months ≈ 45 human years (early adulthood)

- 18 months ≈ 55 human years (midlife)

- 24 months ≈ 70 human years (senescence)

- 30 months ≈ 80 human years (advanced age)

Researchers employ these benchmarks to design experiments, select appropriate intervention windows, and compare outcomes across species. The table enables precise timing of drug administration, dietary manipulation, and genetic modifications relative to human aging stages.

Limitations include strain‑specific longevity, environmental influences, and nonlinear scaling at extreme ages. Adjustments to the conversion values are necessary when working with outbred populations or when extrapolating to other rodent species.

Understanding Disease Progression

Accurate alignment of rodent lifespan with human chronology is essential for interpreting disease trajectories observed in laboratory models. Researchers rely on age‑conversion data to map physiological milestones in rats onto comparable stages of human development, thereby ensuring that experimental findings translate meaningfully to clinical contexts.

The conversion framework provides a systematic method for assigning human‑equivalent ages to rats based on growth curves, organ maturation, and metabolic rates. For example, a rat aged 6 weeks corresponds approximately to a human infant of 1 year, while a 12‑month‑old rat aligns with a human adult of roughly 30 years. Such mappings allow investigators to position disease onset, progression, and therapeutic response within a human‑centric timeline.

Applying these age equivalents clarifies the temporal dynamics of pathology. When a neurodegenerative model exhibits symptom emergence at a rat age of 15 months, the conversion suggests a parallel to middle‑aged humans, informing expectations about disease stage and potential intervention windows. Similarly, oncology studies that induce tumor formation in rats at 8 weeks can be related to early‑life carcinogenesis in humans, guiding risk‑assessment strategies.

Key considerations when using age‑conversion data for disease‑progression analysis:

- Verify that the selected rat strain matches the reference growth parameters underlying the conversion table.

- Adjust for sex‑specific differences in maturation rates that may shift human‑equivalent ages.

- Account for environmental factors (diet, housing) that influence developmental timelines.

- Correlate molecular biomarkers measured in rats with human reference ranges adjusted for the converted age.

By integrating age‑conversion metrics into experimental design, scientists achieve a coherent framework for extrapolating rodent disease models to human health scenarios, enhancing the predictive value of preclinical research.